Anderson Cooper's "Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival"

Heartfelt, insightful & utterly engrossing

Just 207 pages long, "Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival" (2005) by Anderson Cooper is very much worth reading. Something about it feels very important at this time.

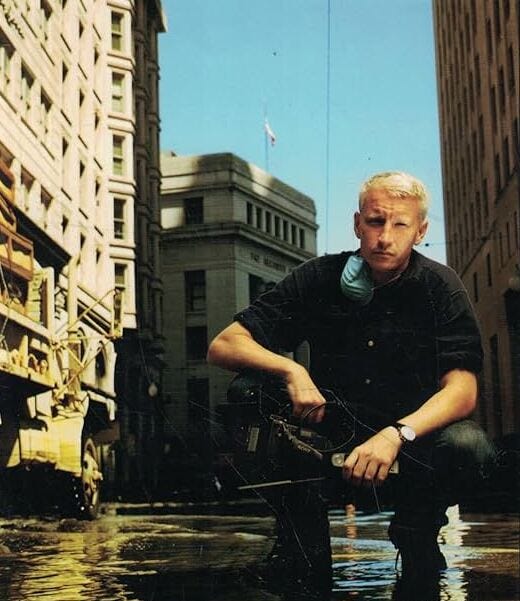

A huge portion of the book is devoted to his coverage of hurricane Katrina as a CNN anchor, and his previous work as a foreign correspondent covering the genocide in Rwanda, the Tsunami in Sri Lanka, and the wars in Iraq, Niger, and Somalia.

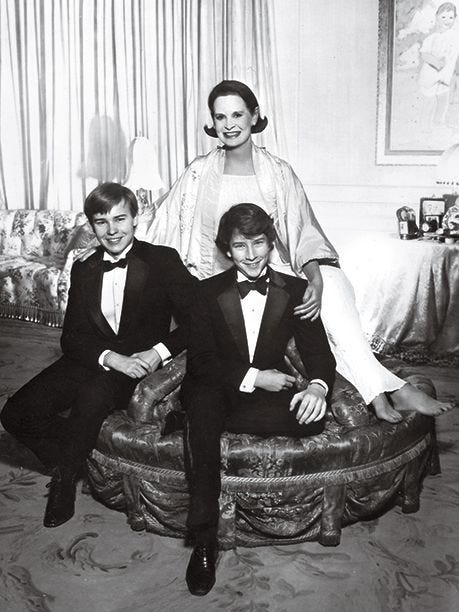

Born in 1967 to a rags to riches screenwriter named Wyatt Cooper from rural Mississippi, and his wife, the heiress and iconic fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt, Anderson Cooper grew up in New York City. His father died when he was just 10 years old and his only brother Carter Cooper died while Anderson was an undergraduate at Yale.

To deal with his grief, he got a job writing for Channel One and then plunged (self-funded) into war zones, determined to become a foreign correspondent.

Similarly, the personable anchor writes that he volunteered to cover New Year's Eve in New York City for CNN as a way to avoid having to socialize. No one would have guessed.

EXCERPTS of Anderson Cooper's memoir:

In the intensive care ward of the hospital in Maradi, Niger....

They die, I live. It's such a thin line to cross. Money makes the difference...

They die, I live. It's the way of the world, the way it's always been. I used to think that some good would come of my stories, that someone might be moved to act because of what I'd reported. I'm not sure I believe that anymore. One place improves, another falls apart. The map keeps changing; it's impossible to keep up. No matter how well I write, how truthful my tales, I can't do anything to save the lives of the children here, now.

I boarded the plane in Baidoa, soaking wet with sweat. I'd been in Somalia less than 48 hours but had shot enough material for two reports and needed to return to Nairobi to write them. I was dehydrated and running a high fever.

I'd finished off the last of my water the previous night. The Red Cross had let me stay in their guarded compound. I'd slept on the floor and considered myself lucky.

...back in Nairobi... I put on fresh clothes, went to an Italian restaurant, ate pasta, drank passion fruit juice, watched the TV above the bar. I'd been there, now I was here. A short plane ride, a few hundred miles, another world, light years away.

...That night, lying on the well-worn mattress in my dingy room, listening to the tap drip and the mechanical laughter of the matatu minibuses on the street outside, I cried. It was the first time in years.

New Orleans' emergency plan requires authorities to provide buses to evacuate the 100,000 residents without access to transportation. No buses, though, are organized to get people out of the city.

Reporting on a hurricane, you depend on your skills for survival; it's all in your hands. You rent an SUV, load it up with water, food, whatever supplies you can buy; gas cans, coolers, and ice are always the hardest to find...you need to be on high ground so you don't get flooded when the water rises.

Katrina comes ashore at 6:10 am, on Monday near Buras, Louisiana. The sustained winds are estimated to be 125 miles per hour, a category 3 hurricane.... The electricity goes out, transformers explode, lighting up the darkened sky with greenish blue flares. I can't see any debris flying through the air; I can only hear it: the snap of tree branches, the twisting of signs, aluminum roofs ripping loose. You can't tell where the noise is coming from or where the debris is headed.

Wednesday morning we're in Waveland, Mississippi.... I'm not shocked by the loss of property; it's staggering, but destruction is nothing new. It's the silence that shocks me. There's no heavy earth-moving equipment, no trucks with aid rumbling past.

I never thought I'd see this here, in America -- the dead left out like trash. None of us speaks. There's nothing you can say.

There are frontlines in America as well, and right now Waveland is one of them.

For the last two nights, I've been a guest on Larry King Live, and listened as politicians thank one another for the "Herculean" efforts they were undertaking.... I don't know what they're talking about....

"Stop thanking each other" I want to yell. "Grab a body bag and get down here with some soldiers!" Instead I nod and listen. Night after night.

Wednesday, I interview [George W. Bush's] FEMA director Michael Brown. I tell him I'm not seeing much of a responses here, and there are bodies lying in the street. It's "unacceptable," he says. He promises h's "working on it." After the program, someone from FEMA tells my producer we can follow Brown around the next day. Later, however, they call back and rescind the offer.

In normal times you can't always say what's right and what's wrong. The truth is not always clear. Here, however, all the doubt is stripped away. This isn't about Republicans and Democrats, theories and politics. Relief is either here or it's not. Corpses don't lie.

...I'm talking to someone back in the office about the woman we left on the street, and I find myself crying. I can't even speak. I have to call that person back. At first I don't realize what's happening to me. It's been years since a story made me cry. Sarajevo was probably the last time. I've never been on this kind of story, though. In my own country. It's something I never expected to see.

...I always told myself if it did happen here, at least we could handle it better. At least our government would know what to do.

In Sri Lanka, in Niger, you never assume anyone will help. You take it for granted that governments don't work, that people are on their own. There's a different level of expectation. Here you grow up believing there's a safety net, that things can never completely fall apart. Katrina showed us all that's not true. For all the money spent on homeland security, all the preparations that have allegedly been made, we are not ready, not even for a disaster we know is coming. We can't take care of our own. The world can break apart in our own backyard, and when it does many of us will simply fall off.

As a child, I used to spend summers at the beach, and I loved to run along the edge of the sand cliffs made by the retreating tide. As I ran, I could feel the sand collapse beneath me, but as long as I kept moving forward, kept running fast, I could stay one step ahead of the falling cliff. That's what anchoring the news is like. You can easily falter, easily destroy your career in a sentence or two. The key is to keep going, keep moving, never forget you're running on sand.

A few blocks from Bourbon Street, we stop at a police station.... A cowboy crew of cops has been holed up there for days. A hand-drawn sign on a sheet of cardboard hangs over the entrance. Fort Apache, it says.

..."We call it Fort Apache 'cause we're surrounded by water and Indians," says a cop with a cowboy hat and swimming goggles around his neck.

Two day after Katrina hit, [the doctor] got to the Convention Center, however, he discovered that there was no medical team there, just evacuees. Thousands of them.

"The smell was overwhelming....They were packed everywhere," Dr. [Greg] Henderson [who was attending a conference at the Ritz Carlton when the hurricane hit] says, "all the way out into the street and pretty much on the other side of the street; it was just one mass of humanity. No air-conditioning [no food, no water], just people, crying and dying. Crying and dying."

The day of the storm, officials at the Superdome had told those fleeing the floodwaters to head to the Convention Center. They said that buses would soon arrive to take the evacuees out of the city. However, no buses arrived until the end of that week.... There was no medical attention and no police presence inside...."

"I'm not sure if I was being more of a doctor or a priest, you know? Because thee's not a hell of a lot you can do with people this sick with just a stethoscope. The best you can do is...hold their hand and say, 'Just hang on , just hang on. I promise something's coming."

...Dr. Henderson picks up a child's shoe, and a few tears run down his cheek.

...five days of anarchy, if you will...general lawlessness.... I think there was a collective attitude of everyone was just murdering everyone down there. 'Just stay away from that area or you're going to die.' "

I am silent while wandering through the deserted Convention Center with Dr. Henderson, stunned that this could have been allowed to happen, and that it took so long for relief to arrive....

"We look at each other with maybe too much hubris and say, 'This is America, this doesn't happen here,' " Dr Henderson says.... "This is disgraceful. This is a national disgrace. Nowhere in this country should that ever have to happen again. But unless we learn from this, it's going to be very ugly 'cause it's going to happen again."

The anger doesn't go away, but it settles somewhere behind your heart; it deepens into resolve. I feel connected to what's around me, no longer just observing.

Here, in New Orleans, the compartmentalization I've always maintained has fallen apart, been worn down by the weight of emotion, the power of memory. For so long I tried to separate myself from my past, I tried to move on, forget what I'd lost, but the truth is, none of it's ever gone away. The past is all around, and in New Orleans I can't pretend it's not.

In Oaxaca, Mexico, there's a celebration called Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead....

I've come to Oaxaca because I wasn't sure where else to go. When I returned to New York from Waveland, I was told to take some time off, a couple of days at least.

...I spend most of the week in Oaxaca sleeping and writing the beginnings of this book, but on Halloween night I head to the city's largest cemetery.

Around one candlelit grave, I count nearly a dozen men standing shoulder to shoulder. They play some guitars and sing out of tune. Some clutch glasses of beer....

I imagine all those whose stories I've told this year returning to their loved ones.... I think about the people whose names I don't even know.... Who would be there to welcome them back?

I picture my own small family sitting around the graves of my father and brother. I suppose it would be just my mother and I. How would I welcome them back to the world of the living? What would I say? I've told their stories, I've kept them close. It's not enough, but it's all I was capable of....

For so long I've been isolated by sadness; by the end of this year, however, I finally feel whole -- connected to both the past and the present, the living and the lost. The world has many edges, and all of us dangle from them by a very delicate thread. The key is not to let go.

By midnight, Oaxaca's cemeteries are crowded.... Children dressed as skeletons and ghouls run amid the graves, asking for candy or trying to scare people passing by. There is so much laughter, even in the midst of all this loss. It's the way it should be -- no distance between the living and the dead. Their stories are remembered, their spirits embraced.