Expectations about how something is written, Part I

Parallels in art, "bad" words & finding your own voice

In perhaps 1999 I read an undeniably good essay in the New Yorker that was just slightly surprising in its approach to language. It felt too packed with words, too tense, almost too much, but it was just different, and yet absolutely superb. While reading it the first time, I laughed aloud! It was a delight to have my own expectations of “good writing” successfully challenged.

The editors felt the need to note that the author had been trying for years to publish in the magazine, and finally succeeded. I wish I still had a copy of it. It’s a much-needed reminder that “good writing” takes many forms, and that we are wise to be receptive.

The essay was sort of the equivalent of a work by Cezanne:

There is tension in Paul Cezanne’s (1839-1906) slightly neurotic still life paintings. You can almost see gravity acting upon the objects in the painting, as if the artist feared he might paint a wrong stroke. This is noteworthy because normally the best artists, like the best dancers, are confidently in the flow. Nonetheless, it’s extremely good.

Perhaps in response (or perhaps not) Salvador Dali’s (1904-1989) innovative still life of scarcity is weightless.

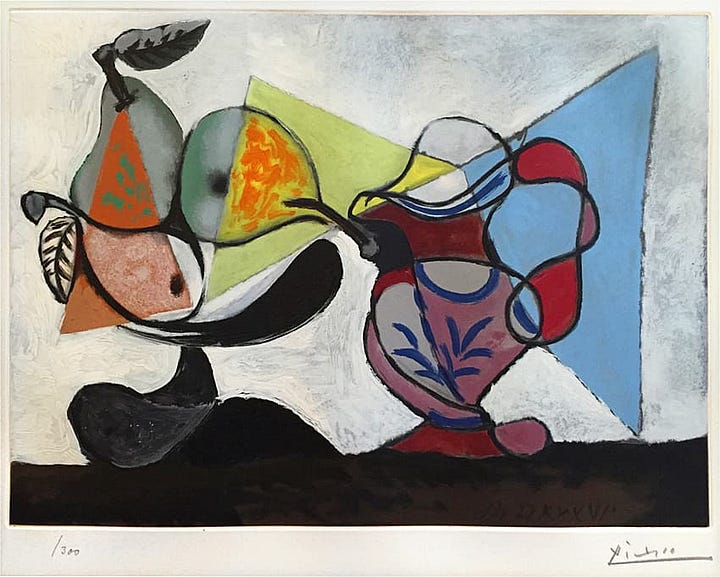

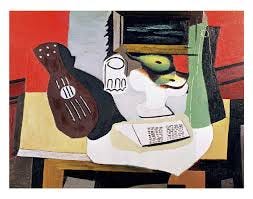

Pablo Ruiz Picasso’s (1881-1973) still life paintings, hands down, are the most innovative and therefore considered to be the best. Picasso would paint many many versions of each work to perfect each part of it.

The take away is that as long as writing answers (solves) a question (problem) for the reader — as long as it has substance — readers can accept a range of styles.

That’s my practical conclusion.

Recently, however, I conversed with Rose Hurst of Memoirist in the Museum about my discovery that some young people consider writing that sounds like it might be from more than 10 years ago “old-fashioned” — like almost all of our posts? She summarized the problem well: “…there are standards, which nowadays have been so blurred that if you actually write correctly, it is viewed as being too formal.”

I know there are many excellent, talented young up-and-coming writers, but some of them have become overly critical. (You’d think they’d be the opposite if they’re complaining about stuffy formality, right?) Surely this is due to overly critical training, the media or social media, or some combination. The change seems to date back to 2001-2004 when America changed its historical trajectory (from sunny optimism to a new victim mindset) that some have dubbed “the Jewification of America.” (Netanyahu said it himself — they let 9-11 happen so that Americans would better understand Israel and that the 9-11 attack benefitted Israel.)

I’d love to hear your own thoughts and insights about any of this.

Unfortunately, this is very clearly happening in all areas of life — now that people have a lot less money and security than before, they are far more critical, it seems, about things that don’t matter, like appearances, fashion, the cut of the clothes, etc. (while ignoring all the things that are wrong that really do matter). Now everyone expects celebs to wear fitted clothing all the time, for example, when this was never the case. Look at old album covers if you don’t believe me.

Maybe it’s a learned helplessness, a way of focusing on something we can control while remaining in denial.

With writing, it takes the form of young people actually complaining about words like trousers and tremendous? (Granted tremendous is a slightly humorous word sometimes, but why be prejudiced?) What might they think of words like bloomers, breeches, britches, chinos, dungarees, pantaloons, rompers and foudroyant?

Even if I might personally prefer little to small, speak to talk, lavatory to sink, to me words are akin to the color palate of an artist, or elements on the periodic table. Each word has entered the language with its own unique history; it’s there because it belongs there with its own unique function.

It seems odd to complain that words might be too old when most of our English words are 500 - 1000 years old, and many are many thousands of years old.

For as long as they are a part of our own personal vocabulary, who has a right to say they don’t belong?

Will our prose one day go the way of Chaucer’s English? For sure, given enough time. I guess it’s just a bit disconcerting to see it happening so fast!

This is the post that spurred today’s musings:

Post Script from the Attic

Did you know all English bad words were originally normal, regular words in dialects considered to be of lower status at the time, like German or Swedish? (How can any word be bad?)

Jerry Jenkins on How to Find Your Own Unique Voice

Best selling author Jerry Jenkins breaks down an easy way to think about developing the unique voice that is personal to you. Plus he offers a simple exercise that will automatically help you identify and capitalize on it. Enjoy!

Great art work.

How surprising to see myself being quoted! Hadn't expected to see that, it was quite a charge! I also wonder if that is the wrong way of expressing it? Not that I'm bothered!

But there is one advertisement that really does bother me as it actually means something different. The ad for Cadbury's Dairy Milk says, "There's a glass and a half in everyone." No, no, no!! There's a glass and a half in EVERY ONE, meaning a glass and a half in EACH AND EVERY BAR. To say it's in everyone means it is in EVERY PERSON. Everyone refers to a group of people! Sets my teeth on edge every time. That's every single time!