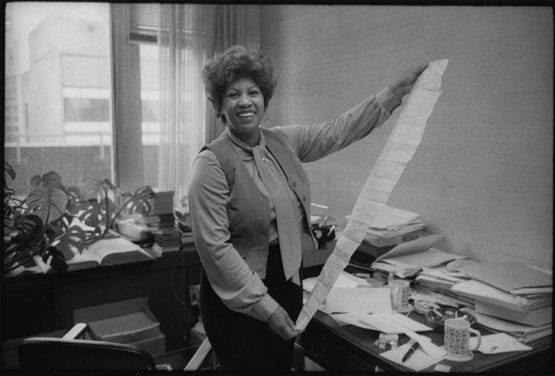

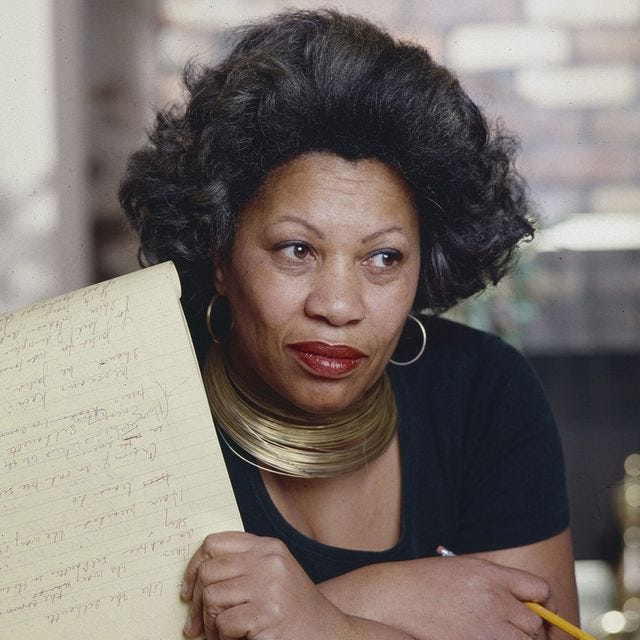

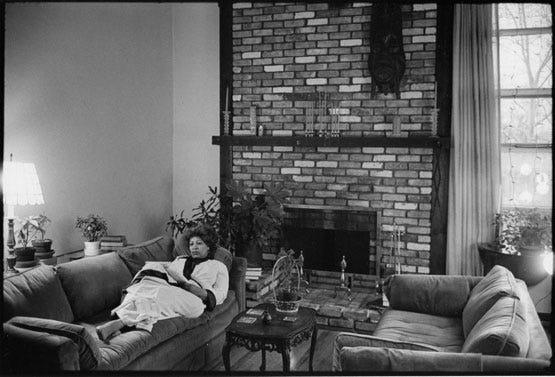

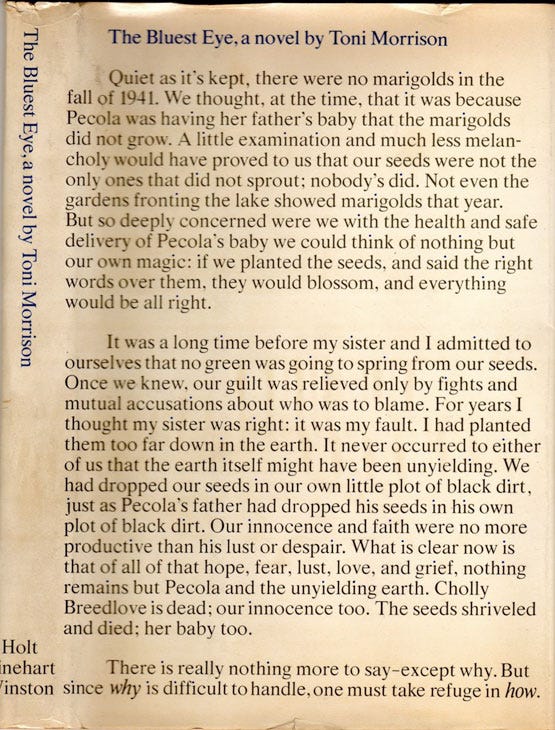

Nobel & Pulitzer Prize Winner Toni Morrison

Writing tips from her years as an editor at Random House

The revision for me is the exciting part; it's the part that I can't wait for—getting the whole dumb thing done so that I can do the real work, which is making it better and better and better. -Toni Morrison

Pull up a chair and a nice cup of Joe or green tea. The magic of writing is that this week, on what would have been her 92th birthday (Feb. 18), we can enjoy the immortal words of Toni Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford, 1931-2019) as she continues to impart her wisdom on the craft of writing.

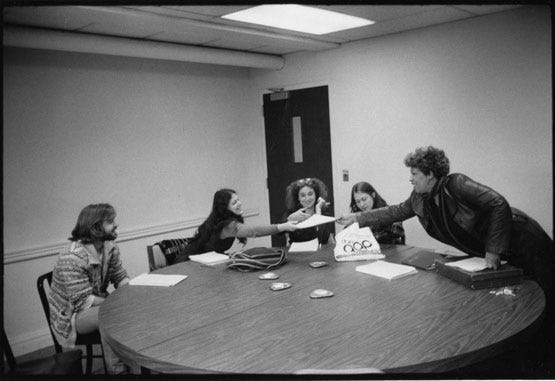

The quotes are either from the Aug. 7, 2019 newyorksocialdiary.com “Jill Krementz Photo Journal” or from 1979 when she was a Fellow on the Bryn Mawr campus. (Photos by Jill Krementz.)

I take control of my characters. They are very carefully imagined. I feel as though I know all there is to know about them, even things I don’t write—like how they part their hair. They are like ghosts. They have nothing on their minds but themselves and they aren’t interested in anything but themselves. So you can’t let them write your book for you.

When I teach creative writing [at Yale University], I always speak about how you have to learn to read your work; I don’t mean enjoy it because you wrote it. I mean, go away from it, and read it as though it is the first time you’ve ever seen it. Critique it that way. Don’t get involved in your thrilling sentences and all that.

In fiction, I feel the most intelligent and the most free, and the most excited, when my characters are fully invented people. That’s part of the excitement. If they’re based on somebody else, in a funny way it’s an infringement of a copyright. That person owns his life, has a patent on it. It shouldn’t be available for fiction.

While I was at Random House I never said I was a writer. First of all, they didn’t hire me to do that. They didn’t hire me to be one of them. Secondly, I think they would have fired me. There were no in-house editors who wrote fiction. Ed Doctorow quit.

There is a certain kind of peace that is not merely the absence of war. It is larger than that. The peace I am thinking of is not at the mercy of history’s rule, nor is it a passive surrender to the status quo. The peace I am thinking of is the dance of an open mind when it engages another equally open one—an activity that occurs most naturally, most often in the reading/writing world we live in.

I, at first, thought I didn’t have a ritual, but then I remembered that I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark — it must be dark — and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come. And she said, well, that’s a ritual. And I realized that for me this ritual comprises my preparation to enter a space that I can only call nonsecular …. Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.

[Writer’s] block comes when I don't understand what's happening in the writing, when the solution is not there yet. When it is there, then other things really fall away of their own accord. There is such a compulsion to it that anything else that I'm doing looks as though it's under water, and then there's this dazzling thing that I'm thinking or writing. And my effort is not to erase the conflict between editing and writing but to pay full attention to the editing and to pay full attention to the teaching, because if I'm really in stride, then I have to hang onto these other things. I don't think that I'm the kind of person who can write without that kind of mix.

The hardest thing to teach writers? Identifying error. Or identifying the bad writing that they do. The problem is, first, to know when you are not writing well and, then, to be able to fix it. It's craftsman-like problems.

I do not teach passion and vision and all of those big, wonderful things which are absolutely necessary for extraordinary writing: I have to assume that my students have vision, passion, integrity, brilliant ideas. But many people possess those things, and the problem is moving from there to the writing, to getting a character off the boat and onto the shore. It's like a magician, you know: when you watch him on the stage you see the rabbit and the lights and the beautiful colors, but the skill is in the false bottom and the dexterity of his fingers. That's what I teach: how to handle it so that the reader is only aware of the rabbit that comes out of the hat and doesn't see the false bottom. That's craft—and hard work.

I bring to the class manuscripts that I have bought, or somebody has bought and published, that are unedited, and I make them do it. They have to identify where it is that the author has gone wrong, where the characters are too thin, the setting and so on—I caution them not to get overenthusiastic about this, but they never listen. They are ruthless when it comes to evaluating other people's things. Then I don't go back to the authors for changes, I go to the students. "You thought the dialogue was flat; well, puff it up!" They start to see what it takes to make a distinction between this person's dialogue and that one's—they don't talk the same.

I remove from [my students] this emotional connection of defending constantly; everything that someone says about your work may not be right, but I say you must pay attention to it. If I am restless about it, something is wrong. I may not know what it is; what I say is wrong may not be right; but pay attention to my unease, or anybody's unease.

When I'm talking to students who want to write professionally, I try to draw from simple analogies: the carpenter who is going to make a perfect chair has to know about wood, trees, the body and how it looks when it is in a sitting position. He should know something about the industry first of all. And then he should pick the right wood for color, look at the quality—in other words, it's a job of craftsmanship. You approach it in a responsible, intelligent way. What has happened, I think—and I would like to place blame somewhere, but I shift so often—is that writing has become almost a celebrity thing in the sense that people don't want to write; they want to be authors. And that's quite different.

Patrick White, the 1973 Nobel Laureate In Literature

If, like me, you didn’t know the name Patrick White (1912-1990), you’re not alone. Born in London, White moved to Australia as an infant. He describes his years at the prestigious Cheltenham College (public and boarding school) in England as "a four-year prison sentence." He started writing plays during his time there.

This. So much this: "I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark — it must be dark — and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come. And she said, well, that’s a ritual. And I realized that for me this ritual comprises my preparation to enter a space that I can only call nonsecular …. Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense."

I love being up early, before anyone else, looking out of the window whilst the kettle boils and seeing that it is still dark and awaiting that transition to light and all that it will bring.

All excellent advice, and what an important distinction to make - writer or author?

Thanks for sharing.